Coffee chemistry

How does alkalinity/acidity and pH work?

What is alkalinity?

Alkalinity is the ability of a solution to resist becoming acidic - which is determined by the concentration of bases (the opposite of acids) present.

While it makes sense for water here, the units used are often non-ideal, being milliequivalents or expressed in term of mg/L of calcium carbonate. Yuck.

Instead, we at Magic Potion like to express the acid buffer present, i.e. the concentration of species that are basic/alkaline and will react with added acid.

This ultimately is expressing the same thing, as the alkalinity of the water is going to be directly related to the amount of acid buffering components we add to the water, like bicarbonate and citrate.

Why does it matter?

Because it will influence the end pH of your coffee cup, sour taste sensations, complex acidic flavours, and this will especially impact black coffees with fruity notes.

What is the role of pH?

pH is a measure of the concentration of free acid (H+) in water.

It is a logarithmic scale, which means that at pH 4 there is 10x as much H+ as at pH 5 and so on. At pH 7 the water is neutral, with equal amounts H+ and OH- in the water.

If we add something acidic like citric acid to the water, it releases H+ to the water, making H+ concentration go up and the pH go down.

All coffee (if brewed in pure water) is going to be acidic because of the natural acids in coffee and fruits in general, like citric, malic, tartaric acid, and ones more familiar to coffee like quinic acid.

These dissolve in the brew water and lower pH.

Our tongue is quite good at sensing acid, giving sour sensations.

If you use RO water there is no acid buffer to oppose these acids coming from the coffee, so naturally pH will go down (probably around pH 5) and the brew will taste acidic, especially as it cools down to 30-40 C where our tongue is better at sensing sour tastes.

Don't worry about pH of the water used

As you'll see below, what is in the water and how it affects pH change during coffee brewing is quite important. Don't worry about the starting pH of water you use for brewing - it will always be above 7, but won't tell you much about the actual buffering capacity.

How a buffer works

If we add something like bicarbonate to the water (a base), it will react with acids added to the water, such as citric acid coming from the coffee extraction.

This will minimise how the pH of the water goes down – it's simple acid <> base neutralisation. Think vinegar + baking soda, same thing going on here.

But this neutralisation is not perfect - pH will still go down as coffee brewing continues. This isn't a bad thing – we probably want the coffee to be acidic. We just might not want it to be that acidic. We can influence the acidity of the final brew by adjusting the amount of acid buffer.

Now, in our case we use substances like citrate and bicarbonate, which just so happen to be "weak" bases that create what we call a buffer solution.

In a certain pH range, the citrate and bicarbonate will resist pH change. This helps us reduce overall acidity and keep pH more stable - which can lead to a more consistent cup as well.

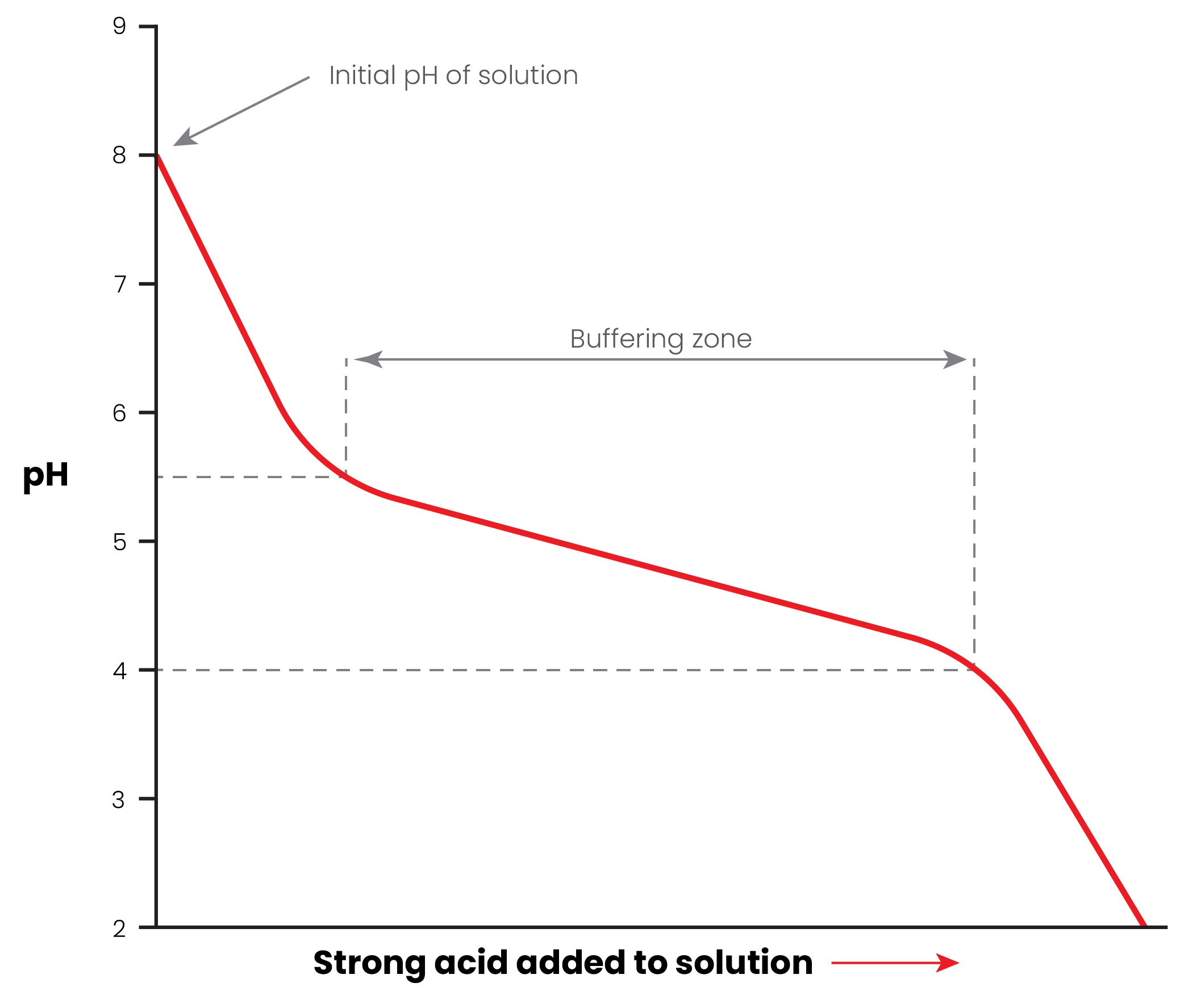

Here's an example diagram showing what happens to pH when you take a buffer solution of e.g. bicarbonate and add a strong acid like hydrochloric:

Note: all these diagrams are just for example, the exact pH's are not accurate.

See how the pH of the brew drops quickly, but then changes more slowly over time because of the "buffering zone".

Without this buffer, the pH will drop faster and further.

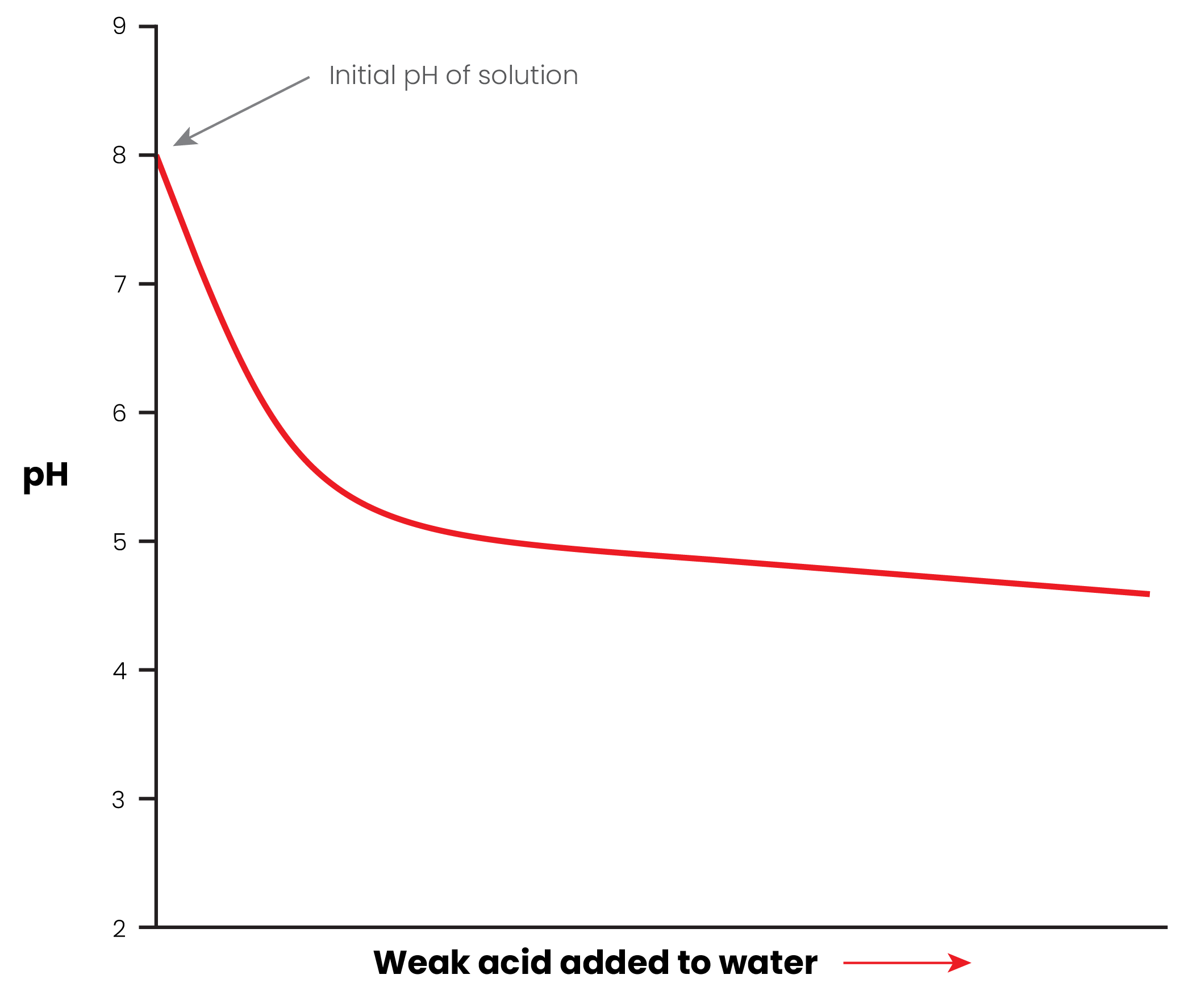

But in our case we are not adding a strong acid like HCl. Weak acids like citric acid do not change pH as strongly.

Here's what it would look like if we added citric acid to pure water -- which is similar to what you would get when extracting coffee into RO water:

Notice how it drops quickly, but then changes slowly after that. But without any buffer, the pH can readily get below pH 5 and keep going down, leading to sour town.

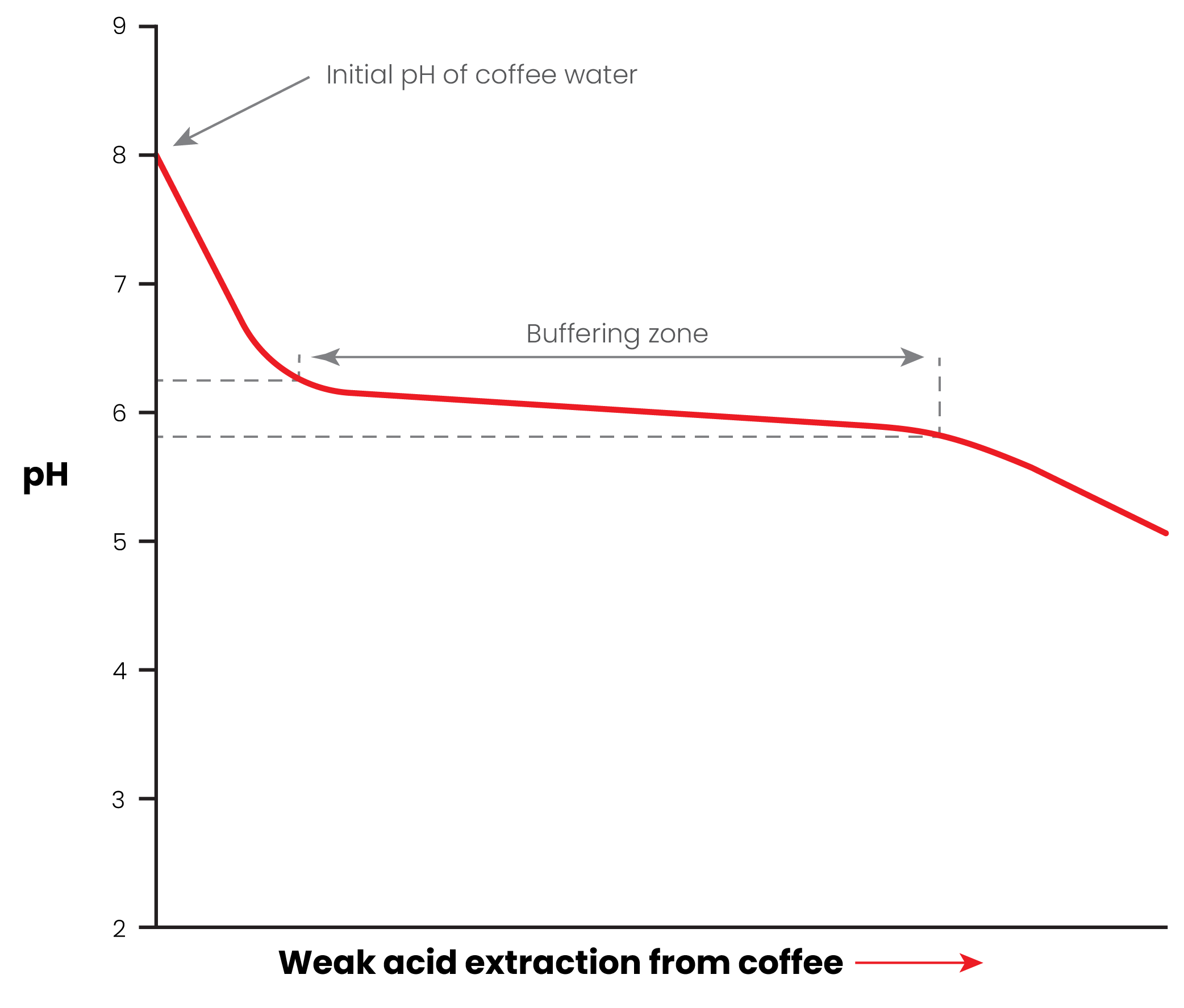

Now, here's what would happen if you had a buffer like bicarbonate AND added a weak acid like citrate:

Here we get that fast drop as usual, but we have a buffer zone where pH changes more slowly. Notice how the pH in that buffer zone is also a much smaller range than before - giving us more consistency with the end cup.

Thankfully, the range of this buffer zone is quite convenient for coffee with bicarbonate and citrate.

With bicarbonate ion, the middle of this buffer zone is at pH 6.4. Citrate is more complex, having multiple buffering steps, and will buffer strongly below pH 7.

For the most part, you can think of citrate and bicarbonate as behaving in the same way, just citrate pound-for-pound is a stronger buffer.

Note with coffee the amount of acid is not actually that great (when compared to soda, fruit juices), and so our buffer will only shift pH by a little bit.

The overall amount of citric, malic, tartaric etc. acids doesn't change, just fewer of them will be in their most acidic form.

However, the flavour of coffee is complex and even small changes in pH and concentrations of citric/malic/tartaric acid can have a profound effect on perceived flavour.

How much buffer should I add?

In some cases, adding NO buffer might give the best result, because the bean + brewing method may give a very low acidity and delicate flavours. In other cases, the brew may be quite sour and need a healthy dose of buffer to reduce this. In the case of milk coffee, we often want to buffer acidity quite strongly, as acidic milk drinks are not as appealing.

So the conclusion? Acid buffer species in water are one of the most important things to consider if you want tailor the acidity of your cup and make that acidity consistent brew-to-brew.

How sour/acidic/fruity flavours work

Pure acidity

To finish this chapter off, let's mention how acidic/fruity flavours tend to work.

For general acidity, two parameters are important:

- The amount of the acid e.g. citric acid

- The pH

The higher the amount of citric acid, the more sour/sharp something will taste.

The lower the pH, the more sour it will taste.

These two often go hand in hand, since citric acid may be what is causing the pH to go down.

However, if you have a buffer present, the amount of citric acid species added stays the same, but less of it may be in its most acidic forms and pH will go up -> leading to less sour taste.

There are actually 4 different citrate species (citrate, citric acid, and two intermediates), so in water they will exist as a blend between these. But the less there is in the pure citric acid form, the less sour everything will taste.

How would you make things taste more sour? You would simply extract more citric acid, by longer extraction or more acidic beans, or reduce the amount of buffer added. Simple as that - play with the levers.

Fruity flavours

From my experience with creating sports electrolyte drinks with fruity flavours, I can tell you there are five parameters that contribute to how "fruity" something might taste and how authentic it might reflect a fruit:

- The overall amount of acids (citric, malic, tartaric)

- The pH

- The ratio of the different acids

- The amount of flavour compounds related to that fruit

- The sweetness from sugars

Firstly, most fruits are acidic, so lowering pH will almost always enhance fruity flavours if the underlying fruit tastes are there. Whether or not that tastes better is a different matter.

Now, different fruits have different acids in them. Citrus fruits for example have a lot of citric acid, whereas apples primarily have malic acid, and grapes are dominated by tartaric acid.

If we take apple flavour compounds and add citric acid... it tastes kind of like apple, but something is off. Likewise if we take orange flavours and only add malic acid, it doesn't quite taste right.

Quite often, sports drinks emulating fruit flavours will use a mix of citric and malic acid as this tends to taste the best. The ratios are up to experimentation though.

The amount of flavour compounds goes without saying -- if there's nothing our tongue senses as grape-like, there simply won't be grape flavour.

Lastly, sugars. All fruits are quite sweet, and this sweetness is part of what we sense and remember as that flavour.

Take a mixture of orange flavour compounds, citric acid, malic acid, salts etc. and it won't taste that much like orange. Add a little sweetness and it can come alive on the tongue.

In coffee, there may be simple and complex sugars that can add to this underlying sweetness and complexity, enough to make fruity flavours detectable and interesting.

A little dose of extra sugars might be needed to make them shine further, such as glucose or maltodextrin, but that experimentation is up to you. Such sugars can also improve mouthfeel.